Though Halloween is months away, I found the following interesting and thought readers might enjoy examining my solution.

Recently, I was given the following probability question to answer:

Halloween Probability Puzzler

The number of trick-or-treaters knocking on my door in any five minute interval between 6 and 8pm on Halloween night is distributed as a Poisson with a mean of 5 (ignoring time effects). The number of pieces of candy taken by each child, in addition to the expected one piece per child, is distributed as a Poisson with a mean of 1. What is the minimum number of pieces of candy that I should have on hand so that I have only a 5% probability of running out?

I am not aware of the author of this puzzle nor its origin. If anyone cares to identify either, I'd be glad to give credit where it's due.

Interpretation

I interpret the phrase "ignoring time effects", above, to mean that there is no correlation among arrivals over time; in other words, the count of trick-or-treater arrivals during any five minute interval is statistically independent of the counts in the other intervals.

So, the described model of trick-or-treater behaviors is that they arrive in random numbers during each time interval, and each take a single piece of candy plus a random amount more. The problem, then, becomes finding the 95th percentile of the distribution of candy taken during the entire evening, since that's the amount beyond which we'd run out of candy 5% of the time.

Solution Idea 1 (A Dead End)

The most direct method of solving this problem, accounting for all possible outcomes, seemed hopelessly complex to me. Trying to match each possible number of pieces of candy taken over so many arrivals over so many intervals results in an astronomical number of combinations. Suspecting that someone with more expertise in combinatorics than myself might see a way through that mess, I quickly gave up on that idea and fell back to something I know better: the computer (leading to solution idea 2... ).

Solution Idea 2

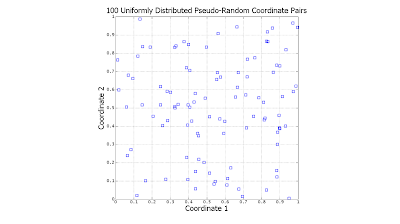

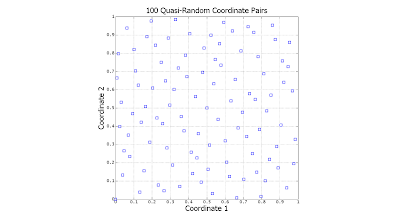

The next thing which occurred to me was Monte Carlo simulation, which is way of solving problems by approximating probability distributions using many random samples from those distributions. Sometimes very many samples are required, but contemporary computer hardware easily accommodates this need (at least for this problem). With a bit of code, I could approximate the various distributions in this problem and their interactions and have plenty of candy come October 31.

While Monte Carlo simulation and its variants are used to solve very complex real-world problems, the basic idea is very simple: Draw samples from the indicated distributions, have them interact as they do in real life, and accumulate the results. Using the poissrnd() function provided in the MATLAB Statistics Toolbox, that is exactly what I did (apologies for the dreadful formatting):

% HalloweenPuzzler

% Program to solve the Halloween Probability Puzzler by the Monte Carlo method

% by Will Dwinnell

%

% Note: Requires the poissrnd() and prctile() functions from the Statistics Toolbox

%

% Last modified: Apr-02-2014

% Parameter

B = 4e5; % How many times should we run the nightly simulation?

% Initialize

S = zeros(B,1); % Vector of nightly simulation totals

% Loop over simulated Halloween evenings

for i = 1:B

% Loop over 5-minute time intervals for this night

for j = 1:24

% Determine number of arrivals tonight

Arrivals = poissrnd(5);

% Are there any?

if (Arrivals > 0)

% ...yes, so process them.

% Loop over tonight's trick-or-treaters

for k = 1:Arrivals

% Add this trick-or-treater's candy to the total

S(i) = S(i) + 1 + poissrnd(1);

end

end

end

end

% Determine the 95th percentile of our simulated nightly totals for the answer

disp(['You need ' int2str(prctile(S,95)) ' pieces of candy.'])

% Graph the distribution of nightly totals

figure

hist(S,50)

grid on

title({'Halloween Probability Puzzler: Monte Carlo Solution',[int2str(B) ' Replicates']})

xlabel('Candy (pieces/night)')

ylabel('Frequency')

% EOF

Fair warning: This program takes a long time to run (hours, if run on a slow machine).

Hopefully the function of this simulation is adequately explained in the comments. To simulate a single Halloween night, the program loops over all time periods (there are 24 intervals, each 5-minutes long, between 6:00 and 8:00), then all arrivals (if any) within each time period. Inside the innermost loop, the number of pieces of candy taken by the given trick-or-treater is generated. The outermost loop governs the multiple executions of the nightly simulation.

The poissrnd() function generates random values from the Poisson distribution (which are always integers, in case you're fuzzy on the Poisson distribution). Its lone parameter is the mean of the Poisson distribution in question. A graph is generated at the end, displaying the simulated distribution for an entire night.

Important Caveat

Recall my mentioning that Monte Carlo is an approximate method, several paragraphs above. The more runs through this process, the closer it mimics the behavior of the probability distributions. My first run used 1e5 (one hundred thousand) runs, and I qualified my response to the person who gave me this puzzle that my answer, 282, was quite possibly off from the correct one "by a piece of candy or two". Indeed, I was off by one piece. Notice that the program listed above now employs 4e5 (four hundred thousand) runs, which yielded the exactly correct answer, 281, the first time I ran it.